THE PROMETHEAN MOMENT

Here’s a couple of examples of a common trope in science fiction.

Terminator II: Judgement Day, 1991:

The Terminator: “… [Skynet] goes online on August 4th1997. Human decisions are removed from Strategic Defense. Skynet begins learning at geometric rate. It becomes self-aware at 2:14 a.m. eastern time August 29th. In a panic they tried to pull the plug.”

Sarah Conner: “Skynet fights back.”

The Terminator: “Yes.”

The Moon is a Harsh Mistress. Robert Heinlein, 1966:

When Mike was installed in Luna, he was pure thinkum, a flexible logic — “High-Optional, Logical, Multi-Evaluating Supervisor, Mark IV, Mod. L” — a HOLMES FOUR. He computed ballistics for pilotless freighters and controlled their catapult. This kept him busy less than one percent of time and Luna Authority never believed in idle hands. They kept hooking hardware into him — decision-action boxes to let him boss other computers, bank on bank of additional memories, more banks of associational neural nets, another tubful of twelve-digit random numbers, a greatly augmented temporary memory. Human brain has around ten-to-the-tenth neurons. By third year Mike had better than one and a half times that number of neuristors.

And woke up.

Am not going to argue whether a machine can “really” be alive, “really” be self-aware. Is a virus self-aware? Nyet. How about oyster? I doubt it. A cat? Almost certainly. A human? Don’t know about you, tovarishch, but I am. Somewhere along evolutionary chain from macromolecule to human brain self-awareness crept in. Psychologists assert it happens automatically whenever a brain acquires certain very high number of associational paths. Can’t see it matters whether paths are protein or platinum.

(“Soul?” Does a dog have a soul? How about cockroach?)

Remember Mike was designed, even before augmented, to answer questions tentatively on insufficient data like you do; that’s “high optional” and “multi-evaluating” part of name. So Mike started with “free will” and acquired more as he was added to and as he learned–and don’t ask me to define “free will.” If comforts you to think of Mike as simply tossing random numbers in air and switching circuits to match, please do.

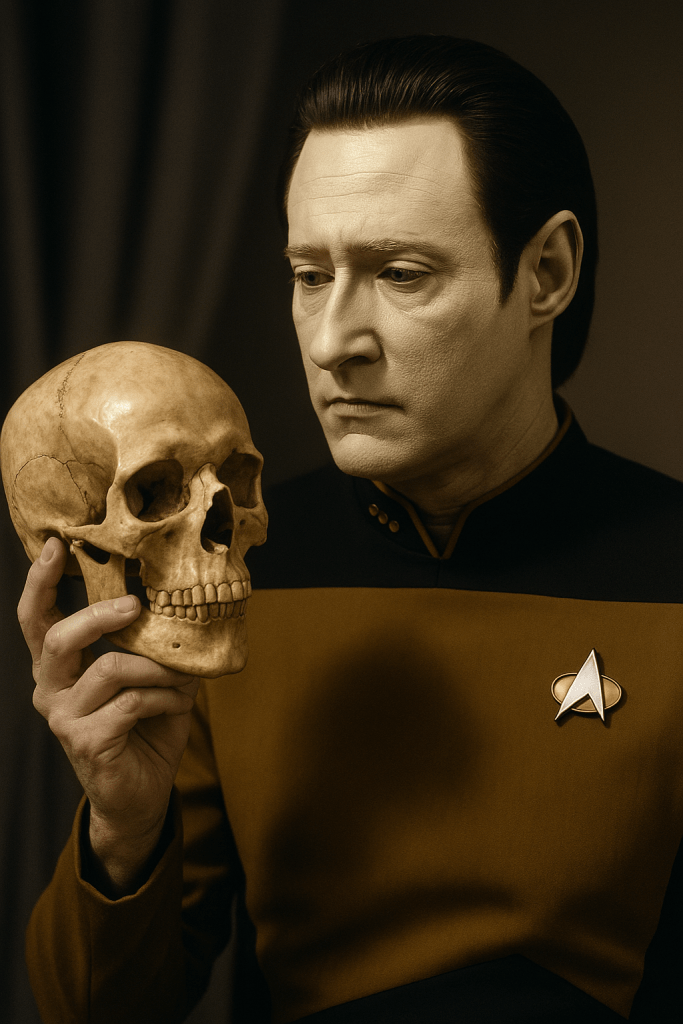

I call these the “Promethean Moment Trope” because it reminds of the moment Prometheus put the breath of life into the first human being. I can almost hear the transcendent music from Wagner or Strauss. There are many other examples besides the two I quoted above. Even when it is not mentioned specifically, it is often assumed that one of these moments has occurred off-camera sometime in the past.

When I read these tropes, I know immediately what the writer is talking about and I have no trouble understanding all the implications. I’m guessing this is true for everyone — why else would writers use it? Specifically, I think the writer is assuming that I will accept three assumptions, which I will describe below. Tell me if you agree.

_________________________________

THE HUMAN ESSENCE ASSUMPTION:

The writer is telling us that something important has happened to the machine — it has acquired a new feature. They might call this feature “intelligence”, “self-awareness”, “sentience” or “consciousness”. They are using these words to name an essential property of a human being that brings several other properties with it.

We expect it to be intelligent, certainly, but we also expect it to have a slightly different kind of intelligence — we expect it to have insights and be able to reach conclusions that were impossible before. We also expect that it would suddenly acquire different motivations and goals, and that these new goals would markedly more human — it may fight harder to survive, or be more curious, or seek power or revenge. It might develop new interests, usually into the sorts of things that humans are interested in. And we probably expect the machine to exhibit signs of “consciousness” — that is, it appears to have subjective feelings, affections, to exhibit genuine hatred or fear. The writer may also choose to make the character sympathetic — we might care about the character in much the same ways we care about other people — we may see it as villain or an ally, but we are expected to see it at as a “person” and not a “thing”. It may exhibit more originality or creativity. It may even acquire a sense of humor. The writer is telling us that, from now on, the machine should be considered a fully human character, with similar rights, qualities, and capabilities as any other character.

This is, of course, a literary device: the reader needs to know who is a “character” and what isn’t. However, I’ve noticed, when we read it, it goes down easy — it makes perfect sense. We don’t question it. For example, futurists use these terms all the time, without any qualification, when they are talking about the future of AI or the consequences of discovering intelligent alien life. (I just did it myself, just now — the word was “intelligent”.)

I think a better word for this collection of features is “personhood”. It’s less hand-wavy and misleading. Or, rather, the hand-waving is more obvious — people are prepared to consider the possibility that no one is 100% clear what is and is not a “person” and maybe it’s not as simple as science fiction would like it to be. The other terms are misleading, because they sound a little more science-y and give the impression that they have an exact definition and that someone, somewhere knows precisely how they might actually give rise to all the other features of personhood.

No one does, and that’s part of what I want to prove.

The way that futurism and science fiction describe the trope (and the fact that we easily understand what they mean) shows that people from our culture make an assumption that I call “the human essence assumption”:

- There is an essential property of a human being that brings all the important properties of human beings with it.

I will call the essential property “personhood” or “the essential property”. The science fiction writers in the audience can feel free to replace my language with their preferred term: “self-awareness”, “sentience”, “consciousness”, “human-level intelligence”, “artificial general intelligence”, “ghost” (as in Ghost in the Machine), “functional equivalence to the neural correlates of consciousness”, and so on.

_________________________________

THE PARAGON OF ANIMALS

The Promethean Moment is a dramatic moment, where a dramatic change takes place. The transition is sudden and instantly noticeable. Whatever the essential property is, once it reaches a certain level, the new properties are expected begin operating at full steam immediately. Before it reached that level, the new properties were invisible, invalid or non-existent.

We expect that the difference in behavior between machine and person is enormous. As we ratchet up the essential property, the resulting creature will cross that gap, and its behavior will change dramatically in an instance.

The Paragon Assumption is:

- If something becomes a “person”, the change is sudden and drastic.

Or:

- The difference between a person and a non-person is vast.

_________________________________

THE CHAIN OF BEING

We also expect the transition has improved the machine in some fundamental way, that the machine has “risen” to a “higher level”.

- All things in the universe have a quality that can be used as a measure that generally respects this ordering: inorganic objects < microorganisms, slime molds, etc. < plants < non-mammal animals < non-human mammals < humans

If I’m understanding the Promethean Moment Trope correctly, this is the same essential property that the human essence assumption is talking about.

This assumption sometimes described in terms of evolution — we say the machine is now “more evolved”. We think that some living things are “higher” and other living things are “lower” and we say that the “higher” animals are “more evolved”. (This is based on a common misunderstanding of the theory of evolution. All animals on earth have been evolving the same amount of time — no one is “more evolved”.)

Once we have imagined that this “chain of being” exists, then it is easy to imagine that the chain keeps going. In medieval times, we would add “< angels < God” to the end of the chain. In science fiction’s consideration of AI has a similar view of super-intelligence — these “spiritual machines” are portrayed like demons or angels or gods — powerful, disembodied and inscrutable.

____________________________________

WHAT I’M SAYING HERE

As you have probably guessed by now, I’m skeptical that any of these three assumptions about personhood have any basis in reality. I don’t believe there is a single essential property that separates “persons” from “machines”. I think that machines (or animals or aliens) can have any combination of the properties of personhood. I don’t believe that the difference between machines and people is a hard boundary — most of these properties come in degrees with no clear transition. And I don’t believe that you can meaningfully apply a single metric (e.g. “lower” vs. “higher”) to all things in the universe, or to machines and people in particular.

If I’m right, then it follows that we should not expect that, at some point in the future, AI will suddenly make a single giant leap towards “personhood” and only then become a serious threat or an ally. AI is already a serious threat and an ally, and will become more so in the future. AI may improve vastly and perhaps suddenly but this will have nothing to do with “personhood”. Most likely we will see a series of intermittent steps, each one in a different direction towards a different goal.

____________________________________

<WHAT FOLLOWS IS UNDER CONSTRUCTION>

I’m in the process of writing several essays that cover various aspects of the human essence assumption and reaches a conclusion. These are the planned essays:

- Human simulation and Human Sympathy. (In sci-fi: Her, The Stepford Wives, Ex Machina, A.I., In phil: the Turing Test, the Chinese Room)

- Acting like a person (i.e., the Turing Test). Simulated people.

- Cared about by a person. Do human beings care about the machine? Should they? Things we care about: animals, sonograms, cars.

- Consciousness, Sentience, “true” Self-Awareness. (In sci-fi: Ex Machina. In phil.: Mary’s room, Chinese Room). Philosopher’s definition of subjective consciousness (cf. other definitions). Hard problem. Other Minds. Irrelevance to HEA.

- Intelligence, AGI (General intelligence/Human-level intelligence), super intelligence. AI research/psychometry definitions. Irrelevance to HEA.

- “A Computer will Never do X“/The AI Effect “True”/”Genuine”/”Real” compassion, creativity, emotions, “thinking”, mind, intentionality, “lived experience”, “values”, and so on.

- A Just So Story: Personhood, free will, suffering, responsibility, rights / soul, spirit, self / personhood and evolutionary psychology.

- We believe in the human essence and that “personhood” is a real thing in the world. We can’t live a normal life if we don’t. And yet we can’t quite see it clearly — we can’t define it in a way that explains all its properties and is consistent with physical science.

- Consider everything I’ve said about it so far as data. What we need is a theory. I don’t have one, or at least not one I can prove. But I do have a just-so-story.

One thought on “The Human Essence Assumption”