Notes on Progress

TIME MACHINES

Human bodies are time machines.

My grandfather, born in 1896, grew up in the “wild west” of California: horses, buggies, the occasional train. Before he died, he flew 400 mph in a jet airliner as big as a building and watched men walk on the moon.

But what happened during my lifetime? There’s no comparison. Transportation is still pretty much the same as it was when I was growing up the 1960s — cars, airlines, trains, astronauts in low Earth orbit.

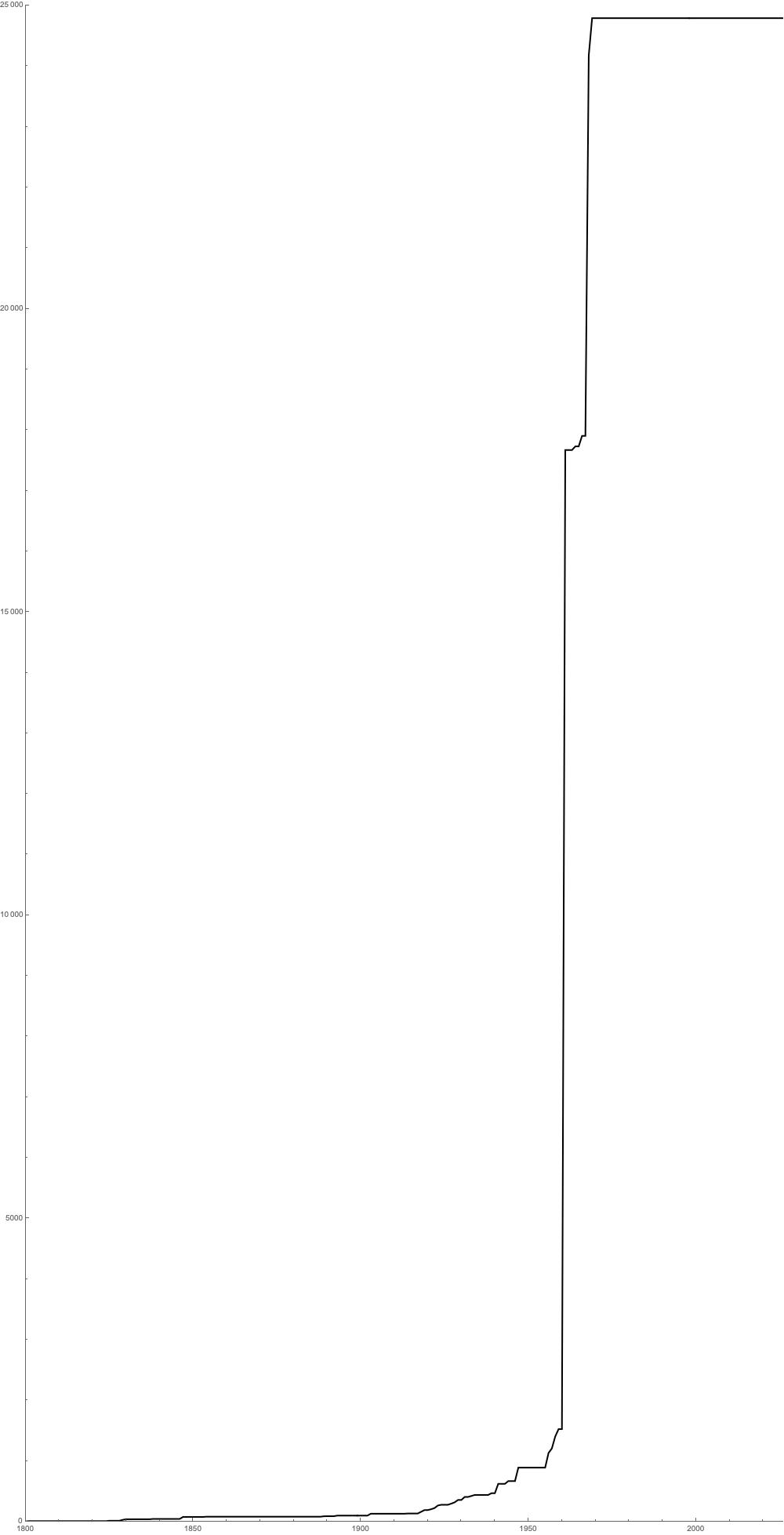

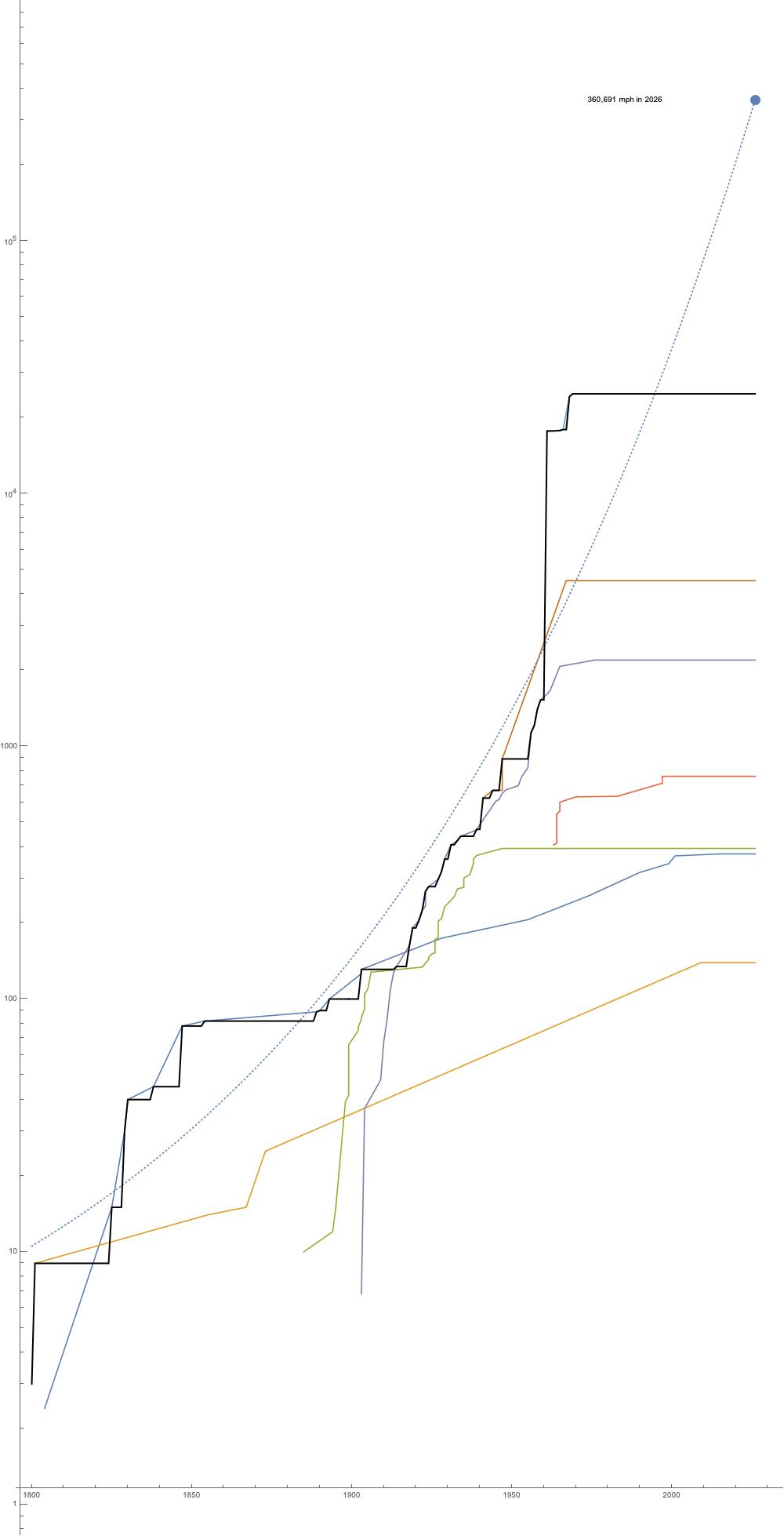

There had been an incredible improvement in transportation starting around 1820. We went from barges and horses to trains, to automobiles, to planes, to jet airplanes, to space craft. The top speeds went from 10 mph, to 100 mph, to 1000 mph to 10,000 mph, improving exponentially over the decades.

By 1970, the fastest vehicle was the Apollo Saturn V rocket at 24,790 mph, the fastest plane was the SR-71 Blackbird at 2,193 mph, and the fastest boat was the Spirit of Australia at 317 mph. If this trend had continued, by now we should have vehicles going 100,000 mph or more and all those science-fiction scenarios from 1960s would have come true.

But as I write this, in 2026, those are still the fastest vehicles. The exponential improvement just stopped. Dead.

Science fiction written before 1970 is positively obsessed with transportation technology, filling the pages of pulp magazines with monorails, moving sidewalks, submarines, flying cars, and, above all, space travel. When Disneyland’s Tommorrowland was rebuilt in 1963, no less than seven rides were dedicated to the future of transportation. In 1969, Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick predicted that by 2001 we would be commuting to the moon and sending men to Jupiter.

All of this made sense — these writers were just extrapolating on the clear and obvious exponential trend line you see in the graph above. But the trend leaves the data behind. The graph poses an important question: the end of progress in transportation was so abrupt, so unexpected, so contrary to accepted opinion of the time — it demands an explanation. Why were we so wrong?

The answer is both obvious and — at the same time — surprising. It’s not hard to map out the technological, economic and political reasons we stopped. It’s much more difficult to get your head around what this actually means.

WHY WE DIDN’T GO BACK TO THE MOON

There are several reasons as it see it: economic, political and technological.

- It’s incredibly expensive. Apollo cost 100 billion or so in 2018 dollars.

- No one has figured out how to make it substantially cheaper. I’ll explain in this in the next section, but the short answer is that we are up against real physical limits in fuel chemistry, rocket science and life support.

In order to pay for it, the U.S. government would need some really, really good reasons to spend all that money. In order for the private sector to do it, there has to be some way to get a return on that investment.

-

The reasons we went in the first place no longer apply.

-

National reputation. We needed to show that our science and industry could match or beat the Soviets, to convince other nations to ally with us in the Cold War and that our ideology was more productive and powerful than communist ideology.

This is no longer necessary, because we made our point, and by the 80s we were winning the Cold War. (But, as Neil deGrasse Tyson said, “If the Chinese landed on the moon, we would be there in 9 months.”)

-

Military R&D. Rocket technology is basically the same whether you are sending up astronauts or sending up intercontinental ballistic missiles. The same companies were building rockets for NASA and for nuclear weapons. Thus, the space program contained a weapons program; some of the money spent on NASA was money saved on building better missiles.

In the 70s, military planners realized this goal could be accomplished for less money by funding missile programs directly. In fact, Congress passed a law, called the “Mansfield Amendment” which discouraged funding pure research without clearly defined military or strategic goals. In this environment, NASA’s budget was cut in half and Apollo’s remaining missions were cancelled.

-

Scientific research. NASA’s space exploration mission did not stop in 1973 but has continued to make extraordinary discoveries with robots like Mariner, Pioneer, Viking, and so on. Robotic spacecraft proved to be a much better tool for scientific research, at far less cost and with no risk to human life. Manned spaceflight is simply not the best way to accomplish the scientific goals.

-

-

There aren’t any particularly compelling new reasons. The U.S. government has no new strategic or economic interest in the moon. Virgin Galactic and SpaceX are betting that satellite launches and space tourism will pay the bills, but a trip to the moon is substantially more expensive and there is no clear way to recover the investment.

WHY SPACE TRAVEL IS STILL EXPENSIVE AND DIFFICULT

Why is it so expensive? Why has been so hard to find a way to make it substantially cheaper?

Space is a very long way up and it takes an enormous amount of energy to put something up there. We live at the bottom of a hole that is 215,000 miles deep. (That’s how far up L1 is, the point where you start falling towards the moon.) This is something that will never change.

Our rocket engines operate at close to 90% efficiency and our fuels are very close to the maximum balance of energy density, weight and safety that is possible, given the laws of chemistry. The Saturn V’s fuel was hydrogen, the lightest element, with exactly one proton. It has the highest mass/energy ratio that is possible; there is no better fuel. This is as far as you can go using chemical energy to create motion. This isn’t just a difficult problem waiting to be solved — this is a problem that has no solution.

This means we need to carry a lot of fuel and rockets have to be huge. Giant rockets, dangerous fuels, the transportation and support to go with it are expensive, and this is unlikely to change using chemical rockets. We’re close to the limit of how much energy we can get using the tried and true method of improving combustion.

The second problem is that space is beyond deadly — there’s the vacuum, the extreme temperatures, the radiation, and there’s no water, no food and no room for error. Living in Antarctica is a million times easier by comparison and no one wants to live there. It’s hard to build a safe place to sleep in space, and that’s never going to change, unless human bodies change.

None of these difficulties will ever change. They are built into the physics of the universe. The amazing fact is that progress in transportation technology has stalled because we ran up against real physical limits.

I believe we will eventually overcome all these limits, but it is far more difficult than the tried-and-true method of improving combustion. There are many possible ways to go forward beyond chemical rockets, but it’s difficult to predict which ones will work. We’ve looked into nuclear explosions that push a rocket into space (Project Orion), space elevators, and a lot of other ideas but they all have problems with safety, energy or cost. But the key point is that these are different paradigms and we can’t improve them at the same steady rate that we improved techniques based on combustion. We don’t know which ones will work, we can’t foresee unsolved problems or unintended consequences. The upshot is that we can’t easily predict how soon these new methods will be delivered, if ever.

ON THE MYTH OF PROGRESS

The exponential improvement that my grandfather lived through was happening for all those decades because we kept discovering more efficient ways to turn fuel into motion. But this paradigm had limits: there is only so much energy you can get out of chemical reaction. When we hit this limit, the improvement stopped.

This is counter-intuitive because it contradicts the myth of progress. We naturally assume that scientific advancement has no limits and that it keeps bringing us innovations at a steady rate. I would argue that rockets (and transportation in general) is an excellent counterexample to the myth of progress. It shows that sometimes there are limits which can’t easily be overcome. Sometimes progress stops.

People think of scientific and technological progress as a journey — a steady walk into the future that never needs to end. I don’t think this is an apt metaphor. Progress is not steady — sometimes it’s very fast, sometimes it’s slow, sometimes it stops all together.

I think progress is more like mining. Someone discovers gold, and then the work goes very quickly for a while — it “booms” in a big exponential explosion. But then at some point, the seam begins to run out and it gradually goes “bust”. Maybe there’s another boom somewhere else. Maybe nothing happens, and there’s no real progress for centuries. Since the 1820s we’ve been mining this vein that has to do with combustion and energy. It gave us exponential progress in engines and power generation for 150 years. But then the gold ran out. We’re near the limits of combustion chemistry and now it’s much harder to make progress.

There’s another boomtown over in the next county, that has to do with information and computing. We’ll see how long that lasts.

TOWARDS A THEORY OF PROGRESS

It’s tempting to believe that progress follows a smooth exponential curve. I think a more careful analysis would reveal that flow of innovation is not laminar but turbulent — that progress moves in fits and starts. Sometimes it races ahead but it can also slow or halt altogether. It can have long periods of stasis and is given to unexpected changes in direction.

Thus, we cannot assume that there is an abstract principle or force that invisibly causes progress.

Three points stand out for me.

- Progress proceeds at a different paces in different areas. Knowledge and practices in some areas are stable, others are in the midst of an explosion.

- We should expect exponential progress in an area to be followed by a period of stabilization. There is no way to be certain exactly when this will happen or how abrupt it will be.

- There is no way to know when a discovery will open up a new area to exponential exploration, or what area will be opened up, or even whether such an area still exists.